Her Ride-or-Die Era

Netflix technology leader Lisa Shissler Smith on turning personal struggles into career empowerment

Lisa Shissler Smith rolled up for our coffee date 10 minutes early driving a Porsche. I screeched in five minutes late in a loaner from my dealership’s repair shop, which had parked my vehicle in a known flood zone during a tropical storm.

Her mind works like that sports car—fast and unfettered. Mine operates like my hot cycle from 1978: A little plodding at times, but it gets there eventually.

She works for Netflix, splitting her time between the Research Triangle Park area of North Carolina and the streamer’s headquarters in Los Gatos, Calif. (With occasional retreats at its Lake Tahoe ranch to talk content development, tech operations, world domination, etc.)

I split my time between a cluttered office in my attic—where I sometimes watch Netflix—and NoRa Cafe in Raleigh.

It may seem like Shissler Smith and I have little in common beyond our 25 years of friendship. But right now, we are more alike than different. After years of family-of-origin conflict, personal and professional compromise, and the starts and stops of motherhood, we have arrived at a specific, bullshit-free moment in our lives as middle-aged women in which we are both doing what we were made to do and consciously choosing the values and places and people with whom we do it.

Or, as Shissler Smith might phrase it, we are both in our ride-or-die eras.

She just looks a hell of a lot cooler doing it.

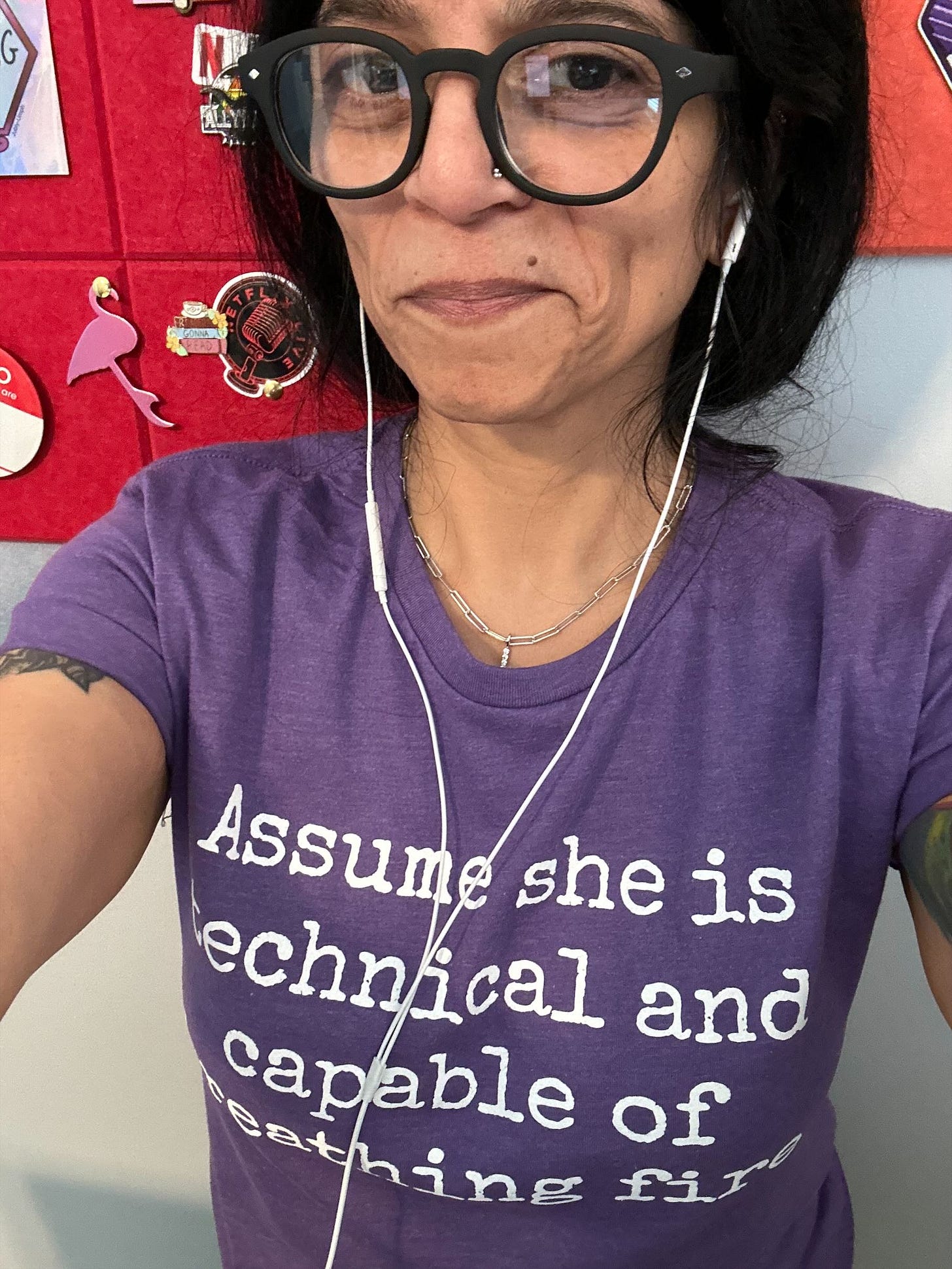

There’s no one better to kick off my three-interview series on defining and redefining empowerment than Shissler Smith, who, as engineering manager for technology lifecycle innovation, leads a team that creates and polishes the processes and products used at Netflix—while also purging what no longer serves it. In other words, she does in her job what she’s been doing in her life.

A former librarian who taught herself to code and then helped pull other women into tech’s future, Shissler Smith shares what she’s learned about turning past struggles into an advantage, creating a workplace that’s more humane for everyone. All that wisdom and more, below.

[If you’re local to RTP, you can see Lisa at All Things Open this weekend.]

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Lisa, who was the person growing up who helped you cope with the control and criticism you took on board from your family?

I know now that it was my grandmother. My mother used to say that she didn’t understand why my grandmother liked me better than my brother because, in an Italian family, the male is always the most important.

That sounds like a script from my life, only with different actors.

Yeah. I didn’t know how to articulate or differentiate it then, but I always felt safe and comfortable with my grandmother. I regret that I didn’t have more time with her. The value of that quiet, consistent, unconditional love—I failed to appreciate it when I had it.

It’s interesting how family conditioning bleeds into careers. I think you and I spent many years transferring the work of belonging in our families—and that’s what chasing conditional love is: work—to our actual jobs. We focused on pleasing others rather than growing and climbing as individuals.

Right, absolutely. And when you add toxicity to the mix, it’s a real problem. My former skip boss at Netflix was a mentor whom I revered in a way I still struggle with. It was very similar to my relationship with my father, just as my relationship with my former boss was like my mother. But it was also a very controlling environment. I took everything he said on board: I will absolutely change to conform to your wishes. I will not speak unless you tell me I can.

His staff was all women, and women often value relationships and loyalty. He absolutely leaned into that. Most of us also belonged to some other underrepresented group. Knowing that we were so grateful for what he had done for us, how he had enabled us to be there, helped him play us like chess pieces—and boy howdy, did that feel bad.

What are some ways your management style differs from the controlled environment you were used to?

My old boss also approached everything from a project management focus. As long as we delivered on deadline, it didn’t matter how we got there. But it very much matters how we get there. Because selfishly, if I break these humans here, I don't get them later. Netflix doesn’t get them later. I don't have a team anymore. That's not sustainable.

Work-life balance is a binary fallacy; it’s never one thing or another. Life is always happening when you’re at work. There’s probably always work cooking in the back of your head when you’re experiencing life. What matters more than an individual’s work-life balance is structuring the team and their work so that if somebody has more life than work on a particular day, the rest of the team can still function, and no one is impacted in an outsized manner. If somebody has a life event that causes an entire project to collapse, that’s my fault as a manager.

So we have a level of flexibility and choice and empathy built in that means people can take the time they need to deal with, you know, root canals and cars that get parked in flood zones. Life will continue to happen, and you will still have to deal with the fallout—even as we prepare our systems for a massive, live NFL event on Christmas Day that we’ve never done before, or a weekly WWE kickoff in January, as we are currently doing. We can plan for an optimal happy path in all things. However, have you ever seen that happen?

It’s never fun to go through the fire of a bad situation to find the one that fits, but because you did, your staff benefits from a more humane workplace.

Oh, I lead with that background as a kind of superpower for creating a work environment with empathy and basic human rights.

But I recognize that being a child of trauma means I normalize many things that others aren’t used to. I’ll talk about difficult issues from childhood in a way that may cause others to react with open-mouthed horror. So I’ve had that a little bit where I’m like, “Oh, yikes. That was probably TMI for somebody who hasn’t had to think about these kinds of things.” But that was just my everyday life.

I get that, and I think about it sometimes when I’m writing here. Unfortunately, though, these themes are not uncommon. The more we avoid talking about them, the more we continue the cycle of not understanding the people around us—who we need to live and work with and, I hope, connect with.

Exactly.

I’ve reached the point where I know if someone reacts with criticism, it’s not about me. It’s something they’re carrying. I will leave space for whatever prompts that reaction from someone, but I won’t own their discomfort for them.

That’s huge. That’s huge progress. We would both usually think, Oh, I did or said the wrong thing.

Because that’s what was reflected to us in our families. But knowing who you are without that busted filter is pretty empowering.

Yeah, that’s very freeing. I don’t know that I do that universally, because I will still overthink at two in the morning, when your brain’s like, Hey, remember that thing that happened in 7th grade? Let’s talk about that right now.

Ha! I mean, staying quiet is the obvious 2 a.m. haunt for me. I have stored every interaction from when somebody has told me to be quiet. That’s happened in my family, in my career, and even in volunteer organizations that I was recruited to lead. I want my weak responses to every one of those interactions back.

Yes, yes, and yes. Same.

Let’s talk about that idea and your career. Do you have advice for somebody who has trouble advocating for themselves in their profession?

I don’t know if there’s one thing, but rather a combination of things. It’s recognizing allies, asking questions about what parameters you’re supposed to be operating under, understanding those, and then learning how to navigate those systems. And it’s more of a trick for women than men because many of the systems are set up to be favorable to essentially your average white male.

In what ways?

The promotion process requires a lot of self-advocacy in ways that women are uncomfortable with. And women tend to do a lot more glue work—that is, to support an entire team rather than leading one thing. My job as a boss is to find leadership opportunities for all of my staff to lead projects and be visible, and then to cheerlead and advocate for them. So it’s not just about allyship; it’s about advocacy. It’s about somebody saying your name when you’re not in the room.

You’ve described needing “ride-or-die” people in your life. We sometimes need that in our managers, too.

Yes, and sometimes you have to be your own ride-or-die person. That means recognizing that you are permitted to occupy space and that that space is valid. While you do have to exert effort to continue to grow and change, you should know that if you have been chosen to work in a place, you do not have to prove over and over again that you are worthy and belong there. You bring something that no one else brings, or you would not have been hired. Own that.

Is that struggle to own worth a problem for women more than men? Or a condition of upbringing?

It’s both, but I tend to see it more in women. Men move more confidently through spaces. I’ve had this conversation with my husband. If I am leaving a place after dark and walking to my car, my thought processes are significantly different than his. Imagine that in every other setting, and the same is true. When I move through an office setting, I have to be concerned with what I’m wearing, how I’m walking, and the pitch and tone of my voice. None of these are concerns for men.

If you’re a woman, it can be a problem if you have a more strident voice. It can be a problem if you have a more high-pitched voice—like one of my engineers, whom people assume is a new grad even though she’s been working at Netflix for four years and leads projects. She’s also small in stature like me, and there is very much a “you must be this tall to be a grown-up” kind of perception.

Clearly, my 61-inch frame agrees with that statement. But at least now I have the wrinkles to back up my age. So, there’s that.

But here’s the thing: In tech, we have two problems: gender and age. Younger engineers reach out to me because I tend to be able to masquerade as different ages. I’m a certain height, I have tattoos, I have easily dyeable hair. People always assume I’m younger than I am, and that’s helpful to me because being a woman in tech is hard, but being an old woman in tech is fucking impossible. Being old in tech is not a thing we value. Being an old woman in tech makes you invisible.

When did you start to recognize that?

Kind of always. I’ve always worked for people who were younger than me—until now. This is the first time I’ve had a boss older than me. But this is also the first time women have occupied every space up my reporting chain, all the way to the top, until right before you hit [CEO] Ted Sarandos. It’s all women.

Wow—talk about empowering against a stereotype.

Right now, I’m in a place where I feel supported. Our organization runs with an amount of empathy that I have not previously found in tech. We had an entire week offsite devoted to mental health and personal support, to struggles with neurodiversity in the workplace—which is prominent in engineering—struggles with depression and anxiety in the workplace, places where you can ask for help and also recognize that you are not alone.

Surprising issues can reveal themselves when you come into your own. You experienced leaner financial years when you were paying more for your daughter’s monthly epilepsy medication than for your rent. “Netflix money” has cured that problem, but it’s also created some lesser dilemmas around the psychology of wealth.

Oh, absolutely. When you carry a starvation mindset—in this case, emotionally, in that I grew up understanding that there wasn’t enough love to go around in my house—you struggle to invest in yourself.

Everything comes back to self-worth.

It does. I spent a lot of time on the phone arguing about $17 with a furniture company, so much so that my husband had to stop me and remind me how much I make in an hour. I am more than willing to use all my resources to pay for stuff for our children, and we finance our families to a certain degree. But I am almost unwilling to accept that for myself.

But you know what I can do? I tip absurdly. Twenty-five percent feels like an insult. Let me hit you with something like 35 or 40 percent because that feels like the right thing: You have made my life less hard, and I would like to recognize that you are doing something for me by making your life less hard.

This is how I'm going to operate and move through the world. I can’t fix all the problems for me or anyone else, but incremental progress is still progress, both in work and in life. Maybe I can contribute to creating the kind of world that, when my kids go out looking for the kindness they’ll need one day when they’re on their own, they’ll be more likely to find it. ♣

Hi friends,

If you’re considering donating to help the people of western N.C. recover from the unfathomable effects of Helene, this story from the Asheville Citizen-Times provides many options for how to give and links to do so. These residents are devastated and looking at weeks without power and more than a month without water, in addition to the damage to homes and property and emotional well-being. Please help them out if you are able. —B

NEXT WEEK: Matt Schulz, who went from debt-riddled twentysomething to personal finance expert for LendingTree, shares his advice for navigating our thorny relationships around people and money.