Highly stressed families experiencing ambiguous losses are too often left on their own to find a way out, because existing rituals and community supports only address clear-cut loss such as death. The couple or family struggles alone to confront the reality of what has been lost and what they still have. In the midst of this psychological turmoil, they must reconstruct their family … and manage their daily lives in a new way.

This is a tall order.

— Pauline Boss, Ambiguous Loss

I wanted to visit a place so alien that it might be confused with a non-life-sustaining planet. A place so singular that it might match our new, strange reality.

The kind of place that, unfortunately, always runs through Vegas.

So the four of us arrived in April 2022 aboard a Southwest plane with dozens of BTS superfans and a pilot-turned-DJ who blasted the K-Pop band’s song “Dynamite” over the tinny intercom. As we repeatedly circled the airport to land, the whiny-whoosh of the jet’s engine and the vocal stylings of Jungkook—shining through both the city and the tiny speaker above me with his little funk and soul—ricocheted mercilessly through my skull.

I just wanted to get to the desert.

I had been craving it, which was an odd thing for a woman who’d lived most of her life near the humid beaches and snowy mountains of the East Coast to suddenly crave: dust and aridity and barren skies and, I don’t know, hairy tarantulas. But that had been the point—or so I had told myself when I began planning this trip months earlier: to visit a landscape so different from what we knew that it might induce temporary amnesia for all that we had lost, the holidays we had spent by ourselves since my disownment.

I wanted little more than that, really: to sit inside the unfamiliar. I wasn’t going to the desert to ascend the friable sandstone of Red Rock Canyon. I wasn’t there to cosplay Alex Honnold and do finger pull-ups from the doorframe of my van.

I wanted to see a glowy sunset or two over a blushing rock formation and then drink a blue margarita named after the Sedona sky.

We started with NyQuil, instead.

“Did you bring any cold medicine?” Janie mumbled from her pillow after we’d rented a car and driven from Vegas to a Flagstaff hotel.

She curled in the fetal position with her hands wrapped around her knees and the cords from her electronic devices spiking from her trunk like a desert shrub. She barked the way she used to at 2 a.m., when I would turn the shower to its hottest setting and carry her tired airways into a makeshift sauna. When her father would lift her tiny, weak frame from the house to the car to the pediatrician the next morning.

“I think,” she groaned, picking up her phone as if it had the answer, “I’m getting sick.”

An hour later, we sat in our rental car in a Walgreens parking lot, eating peanuts and energy bars and waiting for a virtual medical appointment to begin. A tumbleweed the size of a tractor tire cartwheeled past us, brittle and bearish and broken off from its roots. It had carried its seeds of Russian thistle far from home only to wind up in a Flagstaff strip mall off Route 66.

“Yeah,” I whispered into the passenger window, “I get it, friend.”

We left with steroids, antibiotics, albuterol, and Dr. Pepper, and the next morning, Janie was up before everyone else, loudly clanging items on the bathroom vanity, making her footfalls as heavy as possible, sighing purposefully above our snoring, signaling to the rest of us that sleep was over.

“Let’s go, people,” she finally said with annoyance. “I’m tired of sitting around here doing nothing.”

It was 7 a.m.

All those days she lost to asthma attacks and pneumonia bouts as a child had left Janie with little patience for the limits of time or her body. Patched together with duct tape and an inhaler, she became a road runner in the desert, leaving little cartoon poofs of dust in her go-go-go wake.

Later that day, after three minutes at a single Grand Canyon site, Kris had already retreated to the car and away from the sun to sleep, while Janie wondered how long we needed to stay at every overlook “since it’s the same basic idea at every one of them.” Randy lost interest when he realized the rock wall would not let him skip out onto the formations beyond. The two of them walked away, found a bench, and huddled together over a map on his phone, plotting their next move, gazing at the ones and zeros flashing on the screen while the vista before them stood flung open like a Crayola box filled with only Burnt Sienna, Raw Umber and Antique Brass.

I glanced at Randy and Janie and then back at the landscape; at the landscape and back at them. I wondered if I was wrong, if this scene was not as beautiful as I thought it was.

And yet, the scene on the bench held its own interest. For the first time, I could see the partnership these two had created. Now that our family was whittled down, the people we were as a table-of-four—the way we approached the world together and apart—emerged from the thorns my family of origin had left behind.

Randy’s head was bowed, his baseball cap backward, prickly chin stubble reddish-blond in the sun, a cheerful look of concentration spread across his boyish face. Janie’s miles-long, stick-straight, light brown hair swirled tempestuously around her in the wind, strands catching on her artsy, black-frame glasses. The two of them pointed at the screen, volleyed ideas back and forth, and joked with one another.

They were kindred explorers in the desert: active, restless, quick-consuming. They stood up and walked ahead, forever tumbling onward in search of more thistle, more adventure.

“They’re only weeds if you don’t want them,” Randy had always said of the no-name, straggly flora in my neglected flower pots.

I let them go ahead of me, feeling the familiar, bittersweet twinge of belonging and unbelonging. I piled my hair on top of my head to tame the curls that had defiantly returned since I straightened them that morning and secured the mess with a clip. “Always be on the lookout for wonder,” wrote E.B. White, so I turned back to the horizon. I noted the scalpel wounds in the rock and tried to capture them under glass for memory. I needed to wring the view empty of all its meaning.

My sense of exploration has always gained steam when I am out of motion; that’s when my mind becomes electrified. This is why I read slowly. And why I write well in small increments. And why I go to art museums and bookstores and movies alone, patient but expectant. I am hungry for ideas, conveyance, comprehension. I am always begging the world to be more than what it seems, to stand still so I can sort its secrets. I want knowledge, metaphor, meaning.

I am of little kinetic use. Sometimes, I think life explodes before me in words alone.

“Must be nice, sitting over there with your nose in a book,” my mother sniped at me once after Thanksgiving dinner. “Why don’t you get up and help?” I had looked around the room at my husband and my father and my brother-in-law and my nephew splayed out as usual on couches and recliners watching television, and I considered what a bullshit setup it was. I thought: Doesn’t she know what a bullshit setup this is? And then I closed the book, walked to the kitchen, and served the pie.

Years ago, when I first struggled to hold onto my identity in the sweep and swells of family life, Georgia told me that wifehood and motherhood were the only jobs I needed, that I should abandon my career aspirations. Why, then, I wondered, did her craft not seem to fulfill her? Why had she never used her fire and flame to demand the expansion of this canyon before me, the world in vivid layers at her own feet?

How could she not want to hold many truths, many desires, many dreams at once?

I turned, ready to bequeath the canyon overlook to a little girl in a pale blue bucket hat, when I saw it: the brittle-green resilience that had been standing patiently next to me, waiting for acknowledgment. It was a wind-blown juniper tree, its right shoulder jutted awkwardly toward the canyon, its strong obliques saving its tilting trunk from a terrible fall.

Something familiar washed over me.

I had not flown 2,500 miles to visit a strange place.

I had flown 2,500 miles to visit a past life.

♣♣♣

I wish I could tell you what really prompted my mother to say yes to Arizona.

My father had fielded several offers to advance at IBM, to take his big brain to other cities. Each time, by her own telling, my mother told him she would not go, and so, he could not go.

Except this one time. I was 5 or 6 years old. Or rather, I was 5 and then 6 years old.

If we tried Tucson for a year and liked it, we would relocate there permanently. I have no useful memories that include my mother from that time—but I have clear memories of my young self in Arizona.

What was Georgia doing while I was exploring our apartment complex and playing hide-and-seek with two classmates who lived in another building, walking to Dunkin’ Donuts with my dad on Sunday mornings, or dancing like a fool in front of my sister’s mirror while singing along to the Grease soundtrack? Where was Georgia while I was getting in trouble for moving one small muscle after we were told not to move any muscles in Mrs. Silver’s first-grade classroom? Where was she when I was being so social, so independent, so indulgent, so … fun?

And why had she acquiesced to Arizona at the end of the 1970s? My mother didn’t run toward things. She’d never flown or sailed; she only drove on side streets. Though she married a sailor, she had never been adventurous.

What was she escaping? A feeling, a hurt, a slight—as when we moved to North Carolina a decade later?

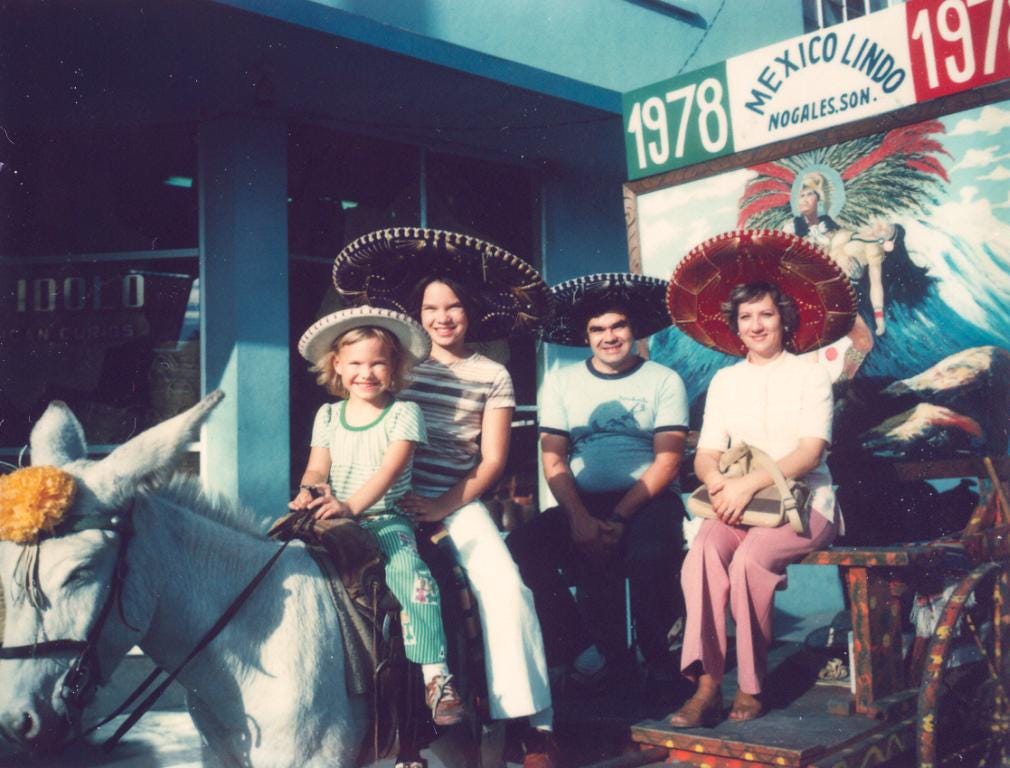

The only proof I have of her desert existence is a photo of the four of us posing on a donkey-drawn cart in Nogales, Mexico. Everyone, including my prim, 35-year-old mother, is wearing a sombrero. Her pink slacks display perfectly pressed creases from her knees to her sandals. She crosses both hands protectively over her purse on her lap. She looks pained, whether from the sun or from her life, I do not know.

The other fact about that picture: I am comparatively ebullient. All teeth, cheekbones up to my eyebrows, hiding from nothing. I am a carefree child who is absolutely living her best life.

Why don’t I recall wearing my Suit of Goodness in Tucson?

“A juniper standing only five feet tall may be 50 years old,” says the National Park Service. “Junipers grow in some of the most inhospitable landscapes imaginable, thriving in an environment of baking heat, bone-chilling cold, intense sunlight, little water and fierce winds. Often they appear to grow straight out of solid rock.”

I had not come here to think about the past, but the past had followed me anyway. I looked at the tree before me, all of its twisted and gnarled beauty, and I wondered if we had met back in 1978 or 1979, when we were both just 5 or 6. I wondered what it knew about survival that I did not. If I had grown up here beside it, would I have learned to bend but not break? Would I have braved the elements naked, with no protective suit, my face turned defiantly into the wind?

Would I be stronger than I am now?

♣♣♣

“Maybe we should just throw our stuff in that one,” Randy had said before we left for Vegas, pointing to a sad, gray, floral Jordache suitcase in the corner of our attic. Somehow after 19 years of marriage, neither of us had mastered the packing game; every receptacle we owned was either too big or too small for every possible occasion.

“That is such a piece of crap, Randy. Are you looking at this thing? Do you know how old this is? I think I got this in 1994.” I plucked an airline sticker off its side. “Look at this. This is a tag from the year I graduated college.”

“Who cares? Who’s going to notice? It’s lightweight, and it’s better than getting something brand-new at this point. We’ll avoid the extra fees at the airport.”

“What if it all falls apart while we’re there?”

“It is not going to fall apart while we’re there.”

“It might fall apart.”

“It won’t.”

I sighed. He would not allow me the comfort of my anticipatory doom. This was a recurring theme between us, and it was one of the qualities that had drawn me to him in the first place: his seemingly untroubled nature. Maybe I should have detailed to Randy how much of my baggage had bloomed alongside that floral Jordache suitcase in my 20s, the era of my life that could give the familial expulsion of my 40s an honest run for its money.

But this pessimist had just wanted to get to the desert. So I relented to the luggage. It’s only a weed if you don’t want it, etc., etc.

By the time we arrived in Sedona near the end of our week, though, I was lulled into such a dreamlike state by the drive down Highway 89A that I had forgotten about the broken pull strap and the rickety wheels on Granny Jordache, who had provided bottomless comic relief as Randy dragged her aging bones across the desert.

Indeed, Sedona provided medicine that I was not expecting, and I am just susceptible enough to mysticism to allow myself to believe in the area’s touted vortexes — “swirling centers of energy that are conducive to healing, meditation, and self-exploration.” I sat on a patio holding a sky-blue margarita, which I am sure had nothing to do with my burgeoning enlightenment, and I was surrounded by towering rocks that glowed orange and pink and tan in the lowering sun, and I thought, I could really live here. Maybe I should live here.

We visited the Airport Mesa overlook as the last light died out over Thunder Mountain and Sugarloaf Rock, and we sat in our car for a long time after, feeling into the silence and the dark amid the tumbleweeds and the dust, counting the twisting branches of juniper trees, watching for falling stars in the sky and hairy tarantulas on the ground.

My mother came to dislike Arizona, of course; she returned home complaining that she had been promised a dry heat but got only swells of rain instead, “garbage cans floating down the highway in a flood.” The landscape was of its own mind. The rocks were already made up, bonded and secure, ancient like our Appalachians back home but more certain of their worth because of how the world prized their healing powers. She could not move them the way she wished.

Or perhaps they could not move her.

“I will never,” she had vowed, “leave West Virginia again.”

But Sedona’s canyons and their crimson spires could overtake the mountains that birthed me if I saw them every morning. They sat self-assuredly in the distance, I thought, wizened and blushed, having already arrived rather than searching, searching, searching for what they might become.

In a crystal shop uptown that boasted of having the “Best Prices in this Reality!” I had chosen a copper-colored pebble called goldstone that glinted in the light. For $8, it teased personal transformation, spiritual protection, harmonizing relationships, and creativity.

I had decided I had use for all of those services.

At the hotel later that night, I secured the stone in a little pocket of our Flagstaff Target purchase: A suitcase with proper wheels. The next morning, as we packed for home, I did not have the heart to toss Granny in the parking lot dumpster. So we left an extra generous tip and abandoned her in the corner of our room next to a trash can overflowing with hotel coffee cups. With her went the dust of my early twentysomething adventures: Boston, Kansas City, Los Angeles, Dallas. Seattle, San Francisco, Miami. New York. Atlanta. Indianapolis. The history of the mystery I used to be.

On the plane home, I pulled on my blissful new noise-canceling headphones—another Target purchase—and called up the artless photo I took of Granny Jordache after everyone had cleared out. A gray bag on a gray floor in a gray room. I studied it instead of the dozens of panoramic images of red rock formations I had taken.

I could not help but wonder if this had become the reason for my desert journey: to lose something. Not to satiate the present, but to starve the past, to bury parts of it in an arid, inhospitable climate where it could not flourish in my memory. Maybe I had come to say farewell to that ebullient young girl in the sombrero, the one who seemed to grow straight out of solid rock. Maybe I had come to leave behind the girl who once belonged to that suitcase, whose wheels had come off at 22 to reveal a tumble of aimless weeds.

Maybe this was the last of her haunting, finally.

Or maybe this was a tall order.

I didn’t know how much of my mother resided within me, or what mashup of us would reside within my children one day as they—I hoped—went out into the world and demanded the expansion they deserved. But I knew that I shared this affliction with Georgia: We had always silenced that which challenged our narratives. Anything too strong to bend to her will, she abandoned. Anything that broke through my protective armor, I fled.

I imagined she thought, when she left Tucson, that it was the last time she would ever run away. And I guess I was sitting on that plane watching the desperate lights of Vegas recede from view, hoping that my own baggage had been swallowed by a vortex in the middle of the desert in the year 2022.

But I know that my mother was wrong about her ghosts. And I suspect mine have miles yet to travel, too. ♣

My favorite part: My sense of exploration has always gained steam when I am out of motion; that’s when my mind becomes electrified. This is why I read slowly. And why I write well in small increments. And why I go to art museums and bookstores and movies alone, patient but expectant. I am hungry for ideas, conveyance, comprehension. I am always begging the world to be more than what it seems, to stand still so I can sort its secrets. I want knowledge, metaphor, meaning.