Before the dawn of this century, I went to a Cowboy Junkies concert outside of Washington, D.C., where lead singer Margo Timmins told the audience what is still one of the greatest love stories I’ve ever heard.

It was about Joseph Furey Sr., a retired ironworker who lived in the same five-room, railroad apartment in Brooklyn for 40 years. He and his wife, Lillian, raised five children in that home, and Furey—who had worked on the Golden Gate and George Washington Bridges after his time as a lightweight boxer in the Navy—spent leisure time playing cards in Prospect Park with a group of friends.

But then Lillian died in 1981, and his park friends began to pass away, too. Over the next seven years, the 75-year-old Furey, who had never visited an art museum, began to affix the surfaces of those five rooms with the dominant motifs of his life—which happened also to be the story of his loves.

He cut out and painted thousands of objects: cardboard hearts for Lillian and for his card-playing friends; bow-ties for a longtime engineering colleague. He incorporated clamshells that his daughters had collected at the beach. Dried lima beans even entered the mix. By 1988, when he left his home to move in with his son, more than 70,000 objects covered nearly every surface of 447 16th St. in Park Slope. It was, Furey told the American Folk Art Museum’s magazine The Clarion in 1990, “something to do to pass the time and get over the grief.”

But the handful of people who walked through Furey’s home after maintenance workers discovered his creations saw more than just an extraordinary hobby.

“It’s a five-room love story,” Barbara Millstein, a curator at the Brooklyn Museum, told The New York Times in 1989.

Which is what the Cowboy Junkies called their song honoring Furey’s art: “Five Room Love Story.”

♣♣♣

I don’t know if it’s a function of age or anxiety over the current moment in this country or just my particular grief fatigue—or everything, just everything in the whole spinning world—but:

It has been a week.

Yesterday, while gathering my collection of discarded tissues to toss in the wastebasket, I followed its trail to my desk, where I stopped to take in my own version of Furey’s dried lima beans.

My sticky notes.

A lot of sticky notes. Let’s be clear: They are not orderly soldiers, lined up for inspection. Neither are they mesmerizing in their repeated patterns, like Furey’s painstaking work. They are instead tackling one another like drunken frat boys in front of my keyboard. They hang off my monitor and lounge like sunbathers under my desk lamp. Some are so old they are faded and curling at the bottom like a jester’s shoe; some are wrinkled in the center from my coffee spills.

My mother had a specific folksy phrase for this sort of behavior; if I had written it down on a sticky note, I could tell you what that phrase was.

One of the owners of Furey’s apartment called the result of his obsession “dreck” after Furey moved out; aesthetically, this is a much more apt term for the circus on my surfaces.

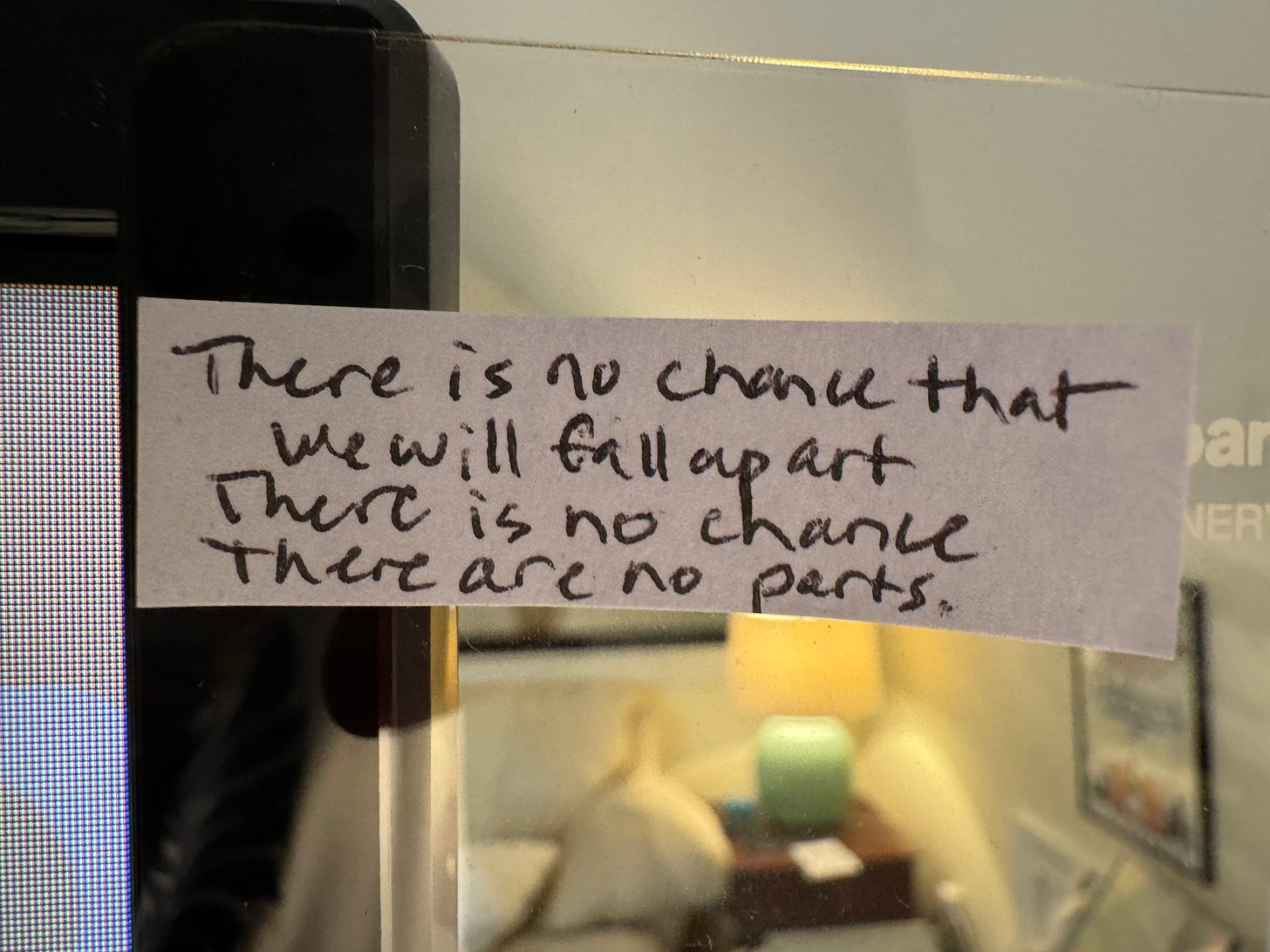

More significant than the mess, however, is what is written on so many of those sticky notes. Most of them are not reminders to make appointments. They are quotes I’ve pulled from books. Lines of poetry I’ve happened across. Answers to questions I’ve asked in interviews for magazine profiles—responses that rang with resonance for me personally but didn’t make it into final copy.

Some are weeks old, some years. At least one, decades.

All around me are the seashells I’ve collected that remind me how to love. That remind me how to grieve. That remind me how to hope. That remind me how to keep it together.

♣♣♣

Last night, I joined my husband on the couch to drink the cup of tea he makes for me every night, even on the nights when he drinks none. Making tea is his version of the painted cardboard hearts that repeated on Furey’s walls. I flopped down beside him with the shaking sigh that follows a great sob: You probably know the sigh I’m talking about, the one that says you have nothing left.

I told him about Joseph Furey and the lima beans and the seven long years of work he did on his apartment in Brooklyn—grief work, really—because he didn’t know what else to do. And then I told him about my sticky notes and their tumbling mess, and I went on about this awful few weeks and the awful world and the terrible worries we share, about sitting in a complicated spot in a complicated country in a complicated time, with two kids who already look at the world through cynical eyes.

I told him that I, too, didn’t know what else to do right now.

Do I keep fighting? Do I keep crying?

Do I stop with the quotes, the sticky notes, the writing? The hope? The only things I know how to do?

“No,” he said, “you keep doing what you do, however you need to do it.”

And then he handed me the tea. ♣

Another beautiful post. ❤️Reminds me that basic kindness carries such weight, especially at this soul-crushing time.

Don’t stop the sticky notes! You and us, your readers, desperately need such inspiration.

Agreed. Even before I read it I was thinking you just need to be you. You are great. You’ve got a good hubby!