My first year on Substack was like freshman year at college

The Freshman 15: gains and losses in the search for community.

~ 1 ~

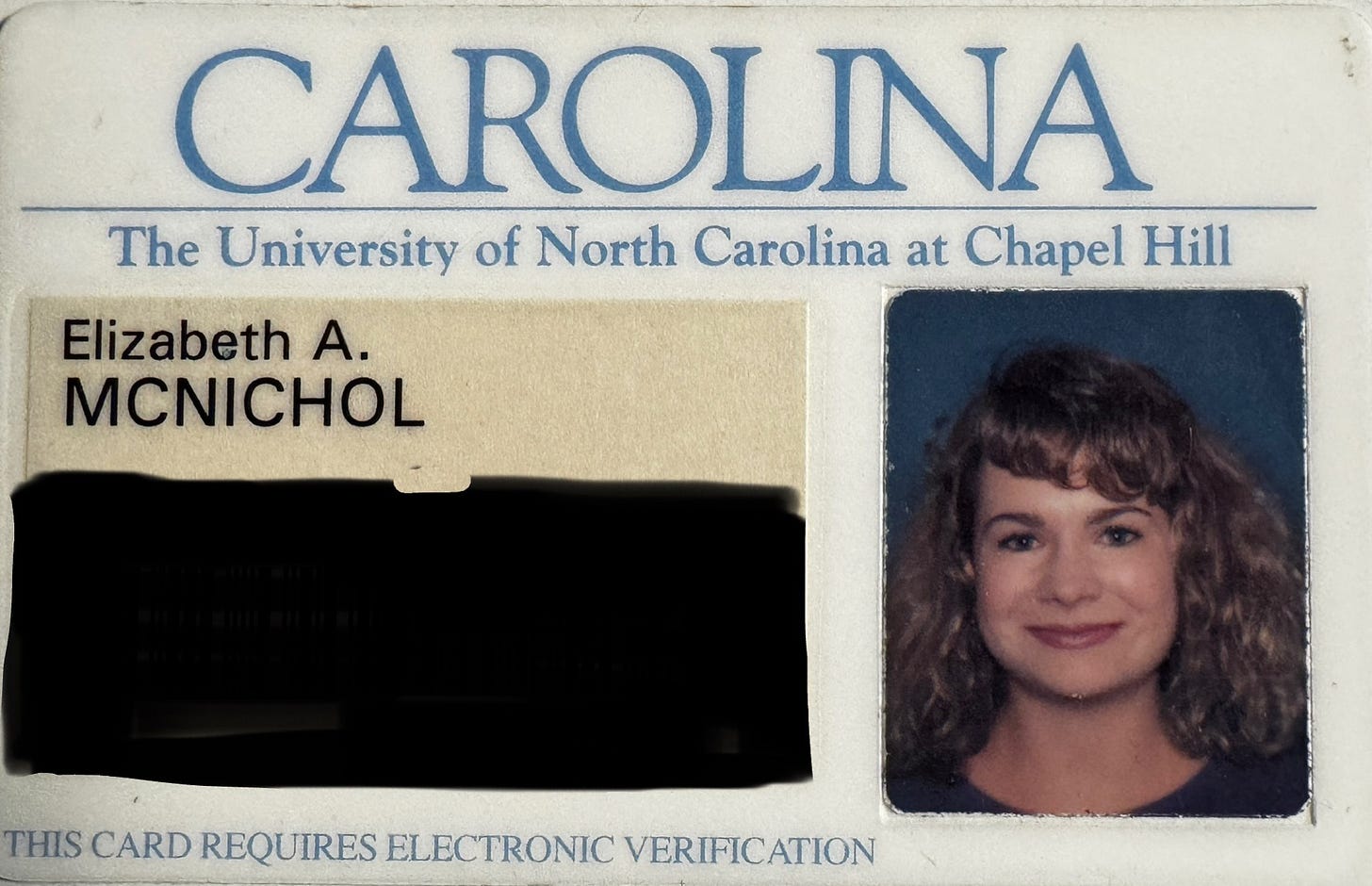

When my orientation counselor at the University of North Carolina—I’ll call him Ben—got around to me with his ice-breaker trivia question, my insides were shaking and my heart was racing. History had shown that I was not fleet of mind under pressure or in new social situations.

“Name a popular place where Carolina students like to meet and hang out,” Ben said, and 25 pairs of apathetic eyes rolled toward me on freshman move-in weekend in 1991.

Ben had the wrong girl.

I had not grown up in North Carolina. My parents had moved to the state two years earlier, when I was 16, and I had stayed behind to graduate from high school in West Virginia with my childhood friends.

But there was never a question that I would return to North Carolina for college; my choices were restricted to in-state, public institutions for financial reasons. Either by miracle or clerical error, I was accepted at UNC.

Academically, anyway.

Culturally, I knew little about Carolina beyond Michael Jordan, the rivalry with Duke, and my conservative parents’ concern that I would be gobbled up by a mob of flesh-eating Democrats in Chapel Hill.

I knew much more about Penn State, where I had attended many football games with my Pennsylvania-reared father. The fight song? I could sing it. Backup quarterback in 1986? You’re looking for Matt Knizner, obviously.

But, “Name a popular place where Carolina students like to meet and hang out?” It was like asking me to solve an equation in an upper-level math course. Or any math course.

Predictably, spectacularly, my attempt at an answer didn’t even hit the backboard.

“Um … the HUB?” I blurted out. It was the student union at Penn State, a name that popped into my head not as the acronym it was (Hetzel Union Building) but as a general term—a “hub” of activity where people hung out. It was the wrong answer for the right reasons. And on any other campus, it would have elicited confused expressions at most.

But raucous laughter rolled across the 8th floor lounge of my dorm. Because in Chapel Hill, there was also a place called The Hub.

And that place was a men’s clothing store.

~ 2 ~

To recap:

I was an introverted, first-generation, essentially out-of-state student living in a high-rise dorm that housed more than 900 people on a campus of 24,000, and the first impression I made on that campus was that of a young woman in a floral-print shorts ensemble who thought a selection of linen sport coats could bring people together.

So far, so good.

~ 3 ~

In November that year, my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer, and I began to spend most weekends at home. Although I was doing well in all my classes, and I loved being a college student—nerding-out in a library was a thing that fit me—I struggled to find my community. The Greek system was not my vibe, but even so, joining a sorority would have cost my parents additional money at a time when extra pennies were unavailable.

I considered giving up. I explained what was happening in my life to my English TA and told her that I was dropping her class. She emptied her hands of papers, interlocked her fingers on her desk, looked me in the eyes, and gently shut me down.

“This is where you belong,” she told me. She was so certain. I took a deep breath and chose to trust her.

~ 4 ~

In a last-ditch attempt to finally find my place on campus, I replied to a classified in the campus newspaper in April for a position as a student assistant in the sports information office. These were the people who handled media requests for UNC athletics, traveled with the teams, published game programs, tracked statistical records and esoterica, and prayed the copier would never jam. To interview, I walked to the only building that was convenient to my dorm on the outer reaches of campus: the Dean E. Smith Center, the basketball arena.

The office had one student position available. I had not expected to be chosen.

And I was not.

~ 5 ~

As finals week approached, I was so exhausted by the previous nine months that I thought I might cry when a fellow first-year offered to share his umbrella with me as we hiked 30 minutes to the other side of campus in an unsympathetic deluge of rain. I believe it was the longest social conversation I’d had all year with someone who was not my (very sweet and also shy) roommate. When we reached his dorm, he insisted I take his umbrella for the rest of my walk. I told him I’d be fine. I wanted to believe it.

Mostly, we discussed his decision to transfer to Stanford. UNC, he said with no ill-will, just wasn’t for him.

~ 6 ~

I’ve been thinking about that difficult first year in Chapel Hill because this month also marks the end of my freshman season on Substack, writing this newsletter that I began after spending the previous two years working on a memoir about belonging and disownment. My chief impetus for putting the memoir aside was this post by Fight Club author Chuck Palahniuk, who advised people like me, in essence, to get over it. Regional writer’s conferences were saturated with under-processed trauma stories, he said. Go write something fun instead, he said. I bet you find the darkness anyway, he said (with humor).

I read his post in the car on the way to dinner with friends. I railed about it on the way home and for the next few days. And because I’ve done a little therapy since my college years, I interpreted my ranting as a sure sign that everything he wrote was correct.

~ 7 ~

My memoir suddenly felt foolish. It was as if Chuck was Ben the orientation counselor, and I’d given the wrong answer to a simple question about where I should be hanging out. I was sitting under a rack of three-piece suits and Florsheim shoes at The Hub, when I should have been tossing back Blue Cups at He’s Not with the cool kids.

And so began my first year on Substack.

I hoped to focus on the good things that remained in my life while also finding a way to thank all the people who had not broken my heart along the way. People who had mended it, or expanded it, or made me believe in magic. I wanted, as Fred Rogers said in 1997, to “take 10 seconds to think of the people who have helped you become who you are—those who have cared about you and wanted what was best for you in life.”

~ 8 ~

This has been a bit like that first year at Carolina: one long search for my community in a new place. Just as it took me a while to grow accustomed to students unironically wearing bow ties and khaki shorts to UNC football games, I am still trying to grasp the culture on this platform.

This one-woman publication has weathered doubts, change, legal threats, and the usual dark nights of the soul. As much as I intended to beat back my memoir’s stories, they kept showing up in my headspace anyway, just as Chuck P. had predicted, and I kept writing about them here, trying to understand them, foisting them upon all of you. It may not have been profitable, it may not have been pretty, and it may not have been worthy of a Brad Pitt feature film.

But damn if every word of it wasn’t real.

~ 9 ~

And that brings us to today, and to perhaps the biggest lesson I’ve learned since I began this newsletter.

A discourse erupted on Substack late last month about who this platform of newsletters belongs to. About whether celebrities who begin their own publications on Substack owe deference or consideration to the small fries still trying to gain attention and build their subscription numbers.

(If you’d like to wade into the weeds on it, feel free to do a search for “Glennon Doyle” on the Substack app or desktop site, and have at it.)

To put it another way (while also mixing my hypothetical sports analogies; just stay with me here), the question at hand was this: Should Michael Jordan be concerned that he might steal Matt Knizner’s potential followers, even when (or especially when) they are playing in completely different leagues and at vastly different levels? Should he care—if you’ll forgive me—that he commands too much air?

Jordan would ask, “Matt who?” count his shoe sales, and move on. On Substack, the reverse happened. Doyle, the celebrity writer, bowed to intense pressure after a week. She refunded all paid subscriptions, removed her publication and exited Substack with the kind of introspection that, I imagine, demonstrates how she became a bestselling author and motivational speaker who had amassed almost 300,000 followers here—most of them women, many of them women who had grown tired of sublimating themselves for others and had found a champion inside her three memoirs.

Some of the women writers who wanted the celebrity to leave Substack said they had found the courage to write about their own struggles because of the vulnerability she had displayed in writing about hers. But now they needed space. They felt diminished by the sudden appearance of the powerful muse who had helped make them.

~ 10 ~

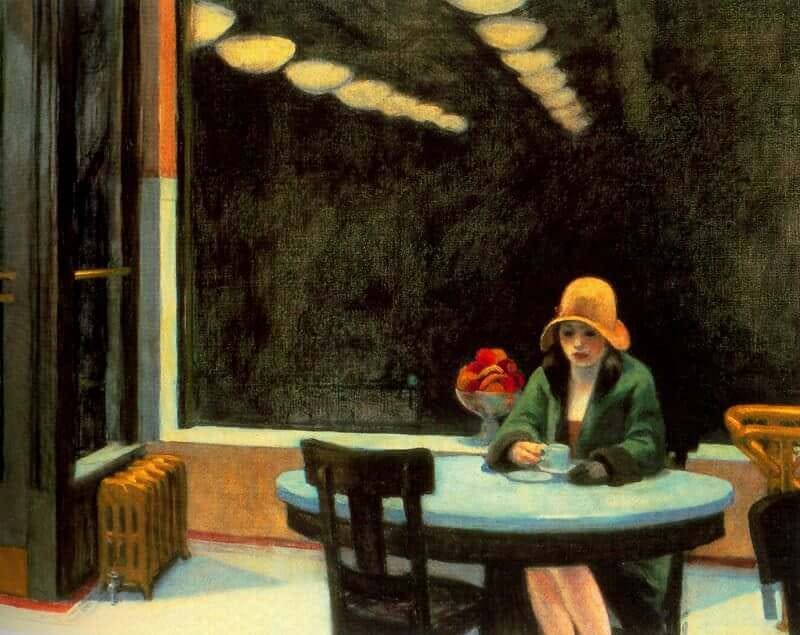

I watched the Glennon Doyle affair from afar. I watched it like a lonely student in the library on a Thursday night. I watched it this way intentionally, not because I don’t care about connecting with more readers, also—I do. But I was feeling around for the story beneath. The one where our vulnerability links us, where we have all been that person who did not belong.

~ 11 ~

I took 10 seconds to think of the people who chose to see me when I could not yet see myself. They are here and here and here and here and all around me. They inspired this newsletter.

~ 12 ~

And since then, I have pictured all of these women—the celebrity and her followers and her detractors—and their real-life struggles away from Substack. The post-it note reminders and on-hold music and children’s hugs and body dysmorphia and sobriety chips and knowing looks from partners and bad memories and missed opportunities and rainstorms of grief that make up any one of their 365 days every year. I have pictured their mothers calling them, and all the bad memories and missed opportunities that haunted their lives, too. I have pictured the teapot whistling in the background of the phone call, screaming at them both to let it go, to get a grip, to get over themselves, to sit down.

And them screaming right back: Shut up. We’re not finished yet. We’re still looking for our HUB.

And I have thought about the stubborn hope that each of these women—the celebrity and her followers and her detractors and their mothers and me—conjures when they sit down to write, or when they ask for more time, or when they go to the polls, on each occasion thinking: This is it. This time. This time everything is going to work out.

And how often, how frequently, it just doesn’t. How, most days, whether you are known by all or known by none, you could cry for an umbrella.

~ 13 ~

This is why I write.

This is why I have not given up.

We are illogical messes. We hope when everything tells us to stop hoping. It’s what I love best about human beings. We are untidy. We are fascinating. We are worth learning more about.

I rage and moan. I thrash and toss. I get angry. I get sad. I suffer from the poverty of my melancholy. Then, I grow. I am not a robot. My now-20-year-old daughter says that I seek the rush of “emotional adrenaline.” I’ll wear that badge. It tells me my heart is still in the game, and I am more than just ones and zeros.

It’s important that we keep reminding ourselves that we are not algorithms, not brands, not commodities destined to be in perpetual competition. We live and work and consume the surfaces of those contrivances, but they do not live inside us. My lungs are not sponsored by Amazon; Substack does not own the title to my heart. What we do will be ranked and numbered whether we like it or not, but who we are does not have to be.

~ 14 ~

I keep coming back to this, to the beginning of my sophomore year at Carolina, which is the end of this story:

The phone rang during the second week of classes. The student who had been chosen over me for that part-time job in the UNC athletic department had to bow out, and I was second-in-line on the depth chart. I was his back-up.

I was Matt Knizner, but on the right campus.

That job changed the trajectory of my life. Because that department of 12 students and five full-timers became my family over the next three years and beyond. It saved me from the poverty of my melancholy. The position gave me stories to write that won scholarships, internships, money for a down payment on my first crappy car. It helped me find my best friends and land my first full-time job.

Those things didn’t arrive in my life because I had cracked a code. They happened because I had found people I could trust, in a place where I belonged—and yes, I even had fun doing it.

It was a deluge of good.

~ 15 ~

One day, embarrassingly true to form, I nearly breezed right past the one man no one breezes past.

I had walked across the hall to get a cup of ice for my Diet Coke from the kitchenette in the Carolina men’s basketball office, a habit I’d developed to stay awake. He was standing there alone in the waiting area, in a suit and tie that was probably not from The Hub, with no entourage in sight.

From her desk, office secretary Angela Lee slid her eyes from me to Michael Jordan and back to her work with a bemused expression. I was back in the 8th floor lounge of my freshman dorm again, speechless, except this time there was no Ben and no mocking laughter. Just the man whose name is synonymous with the school I once thought I would never belong to, looking directly at me and smiling.

And it was nice to be seen. ♣