A lost aunt, a beloved uncle, and the games we play for love

Visiting the ghosts of Happy Valley.

I was a grade-schooler the evening our house in West Virginia was robbed. It was a rainy Valentine’s Day, and we were at an elementary school basketball game when thieves pried open a side door whose deadbolt was a heavy, oversized chair.

I suppose our little house was a mess when we returned home—jewelry and electronics missing, closets tossed—but what I recall with clarity is the muddy outline of a man’s shoe on my fastidious mother’s red ottoman and the eerie sense that we had just missed its owner.

The four of us piled into my parents’ bed that night and the next. We were on edge for months afterward. So, when we awoke one night at 2 a.m. to pebbles clattering against our windows, my mother panic-screamed. My older sister and I scattered behind furniture like high school kids hiding from the cops in a John Mulaney bit.

Maybe my father grabbed a baseball bat. Maybe he went to retrieve his hunting rifle. Neither was particularly his style—and neither, it turned out, was necessary.

“Geor-gia!”

The pebbles began to talk, whispering loudly from the street in a familiar sing-song, carousing with the owls in the moonlight.

“Ted-dy! Geor-gia! It’s us! It’s Aunt Margie and Dan-ell!”

My gawd, as they liked to say in my father’s family, Aunt Margie. Of course.

Tall and rollerskate skinny, with flashing blue eyes and great style, my great-aunt emerged from the shadows of our carport that night with her bemused and genial husband, Dan, tagging along behind. They had driven 20 hours from their home in Rapid City, S.D., gotten a little lost along the way, and neglected to warn us of their impending arrival.

That she awakened us with a Shakespearean flourish made perfect sense. If my father’s mother was a reclusive nest of spun sugar, her younger sister, who biked 5 miles a day into her 80s, was a box of Cracker Jack and a cloud of cotton candy. She crackled with mirth and mischief. She never doubted she belonged anywhere, any time of day or night.

I loved her more than I can say.

She became my surrogate grandmother over the last two decades of her life, when all of my family-tree grandparents had passed—after Dan had passed, too. She never had children, but she had helped raise my father in Altoona, Pa., before she moved west. She adored him as though he were her own. And so she adored us.

Each year, she strode in with her flamingo elegance, her plaid stretch pants, her giant clip-on earrings, and a tiny hitch in one of her hips. She hugged and hugged and hugged us. She was completely irresistible and suspended in some bubbly bottle of unapologetic verve I haven't seen since.

She was a marvel.

And then, on October 18, 2013, she disappeared.

♣♣♣

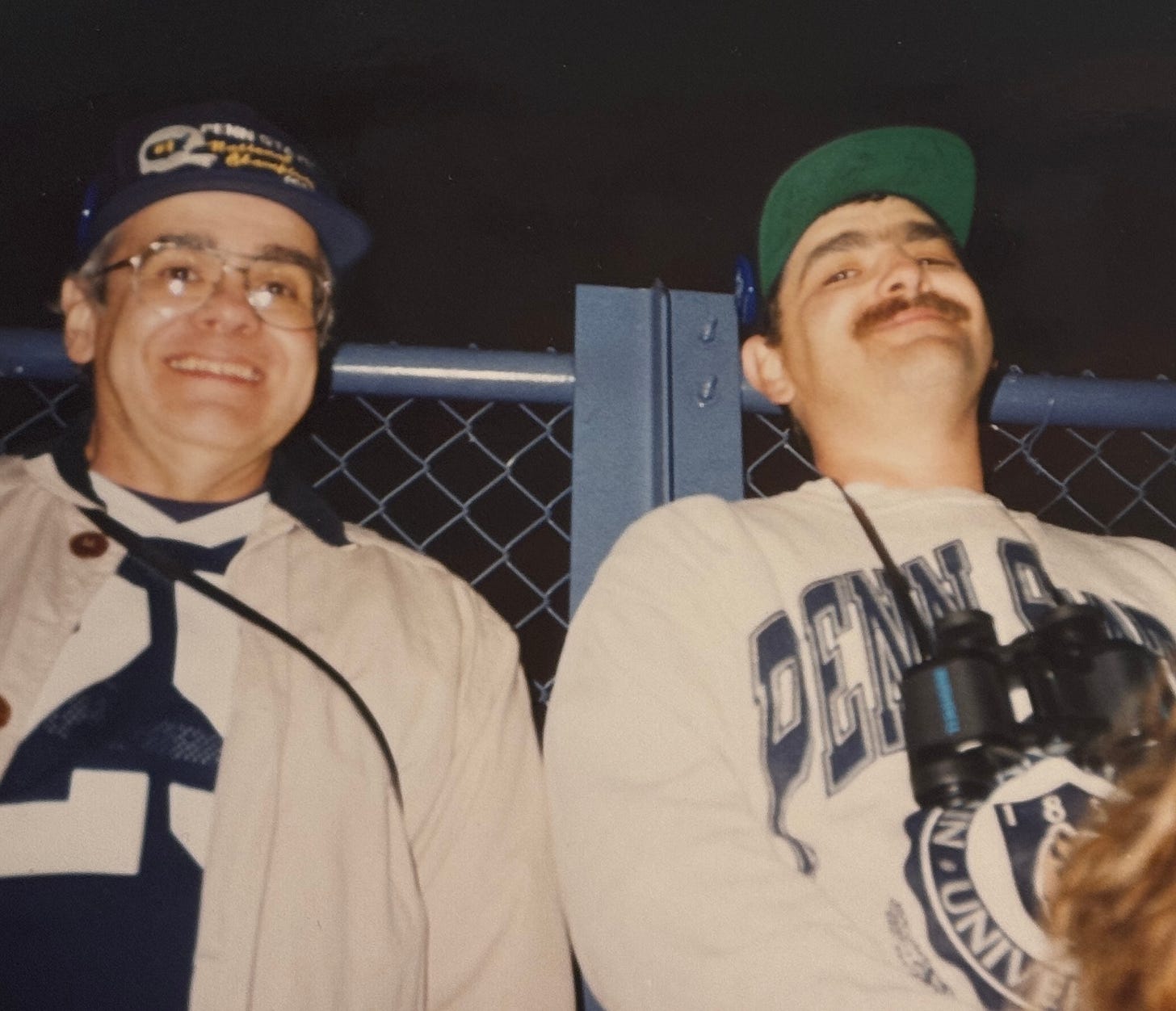

I was crazy about my Uncle Jon, the youngest of my father’s three siblings, and the only member of his family to come close to matching Margie’s carnival-ride magic. The keeper of four Penn State season tickets, a Green Bay Packers fan with a Chicago Bears mustache, and my occasional pen pal, he made frequent cameos in my college writing—beginning with my undergraduate admissions essay for UNC.

When I was a kid, he wrote to me and implied that my father—ten years older than him and a stickler for rules—would meet trouble if he didn’t bring me to games. His tickets were often spoken for by older relatives, but Jon knew what it meant to me and would always find a way to get me in.

“I’ll take care of you,” he wrote. “Don’t worry about a thing.”

Beneath his Ditka ‘stache was a soft heart. He understood what it meant to be the one most likely to be left behind.

Jon was 3 when their parents divorced and their dad moved out. He was 7 when my father left home for San Diego and joined the Navy. He was 13 when he handed my mother—his new sister-in-law, still in her wedding dress—his Mad magazines as a gesture of welcome, or as a test of her fitness, or as a plea for her affection. When his older brothers left Altoona for other cities, other states, other lives, Jon stayed behind, worked for the railroad like his father and his father before him, and bought a home one block over from where he grew up.

He stayed behind. But he also showed up.

When my father underwent cardiac procedures, he drove down to sit with us in the waiting room—first to West Virginia, and later to North Carolina—sometimes leaving as soon as the surgeon emerged with a thumbs up. He briefly met a student with whom I clicked in college and remembered him years later, asking after him. When we talked about something besides football, we talked about hearts—his or mine or someone else’s.

One way or another, it was always about hearts.

Like my Aunt Margie, he made my otherwise mysterious, often unknowable paternal family come alive, placing me squarely inside that universe and making me feel as though I belonged.

And yet, and yet.

He was the reason I never got to say goodbye.

♣♣♣

I don’t know the psychic undertow of my paternal family very well. But I know it exists, daring its three brothers to stand stock-still at its edges. And that is where they have always stood in my eyes, three young boys avoiding the pull of deep emotion. Three young boys, now grown and grayed, who went their separate ways in adulthood and came together only for football games, weddings, and funerals.

But not all funerals.

By the time I heard she was gone in October 2013, Aunt Margie, who had moved back to Altoona, had been buried for a month. Neither of my father’s brothers had contacted us when she passed. It was as though thieves had pried open a side door and left without a trace—no muddy footprint, no tossed closets. They vanished with what mattered most.

I suppose there were estate disputes among the brothers. I suppose you know these things are rarely about money. They’re about the unacknowledged undertow, the perceived debts of affection across a lifetime, and the scarcity of love. They are about disempowerment, and they are better settled in life than in grief.

Maybe for Jon, it was about staying behind. Maybe my father, who was ill-equipped for conflict, missed a call, a message, a social cue. I don’t know. I just know how much it hurt.

But so did this: The day after we heard the news, my parents and sister called me from I-95 North. It was a Saturday. They were on their way to visit Margie’s gravesite in Altoona, they said. They had not stopped to pick me up or invited me to join them. They had left me behind.

Margie had disappeared, it seemed. And for my family, so had I.

I ignored my own undertow for many years after. In photos, you can see it: the talisman I donned like armor to protect the tenderest part of me from going under. It was a life-preserver necklace, purchased after Margie’s death, that I began to wear with intention to family gatherings right up until the day I was disowned three years ago.

Earlier this month, on a Friday morning, I clasped it around my neck again and settled its gold pendant on my heart. Then I climbed into the car and drove north on I-95. I went to toss a few pebbles at the past.

♣♣♣

Reasonable people may balk at the notion of an athletic team functioning like a family’s powerful matriarch, forcing its children to stay in touch. But I have often wondered if my father would have been connected to his family members in later years if not for their shared love for Penn State—a school that none of them had attended.

Would I have known his parents or his brothers or Aunt Margie at all if the Nittany Lions hadn’t practiced once upon a time on the Altoona High School field, cementing a family obsession?

I don’t know. But almost every memory I have of his family runs through State College.

I did not drive to Pennsylvania this month just to attend a football game for a team that is irrevocably entwined with the ups and downs and love and distance of one-half of my origins.

This time, I also came to Pennsylvania to thank my great-aunt for her pluck and her plaid and the hitch in her hip that I’ve likely inherited. I came to thank her for being my platinum example for living, a woman who modeled independence and empowerment and unconditional love. I came to leave pierced earrings at her hilltop gravestone because, like her formerly pleasing great-niece, she long ago earned the right to live without fear of being punctured.

I came to tell her that she had not disappeared. That I had not forgotten her.

But you cannot know my father’s family without knowing Penn State. And if you’re me, you cannot grasp what’s left of that family’s meaning without returning to its confines. It shouldn’t be that difficult. It shouldn’t be that emotional to walk into a stadium as familiar to you as your right arm.

But it was, it was.

Because all of the ghosts were out. The chants of “We Are … Penn State,” the video clips of heroes past, the audio of the roaring lion, the plain uniforms, the fight songs I know by heart …

Before kickoff, I had reminded my husband that we would stay until time expired, that McNichols do not leave games early. For almost four quarters, he watched me crane my neck up and across the expanse of fans, watched my knees bounce with nerves, tracked me searching for evidence of my past. Finally, with two minutes to play and the Lions leading 27-3, he set his drink down and rose from his seat.

“Let’s go,” he said gently.

I don’t know who should receive forgiveness and who should not. But I imagine that, behind my uncle’s front porch in Altoona, festooned with Penn State and Green Bay Packers banners, there are locked rooms of hope that mingle with family shadows, just as there are in mine. I love my uncle for his complexity, for the riled and roiling depths of his unknown stories, for the letters we once exchanged, for the way I don’t know his specific pain but understand its presence, the way he leaves a little opening for me to see inside if I am willing to look.

I’ll take care of you. Don’t worry about a thing.

I am always willing to look.

Because I need everybody. I need my ghosts and my flesh, my saints and my sinners, the entire messy history of my life. So much was taken from me when I was disowned; sometimes, the greatest power I have is holding on to what’s left.

We have this problem in my family, this idea that we need permission to extend love and to feel love in return—a green light, a fair catch signal, an advance warning of arrival.

But maybe Shakespeare knew best.

I followed my husband across four sections of the Beaver Stadium bleachers as the final seconds of the game against UCLA ticked away, as the Bruins made their way to the end zone. We limboed under railings, we scooted through emptied seats, we looked up instead of down.

“Is he there?” Randy asked. “Do you see him?”

I did. He was sitting alone in Row 90, the same row he always snuck me into as a kid.

I climbed toward him. When I tapped him on the shoulder—when I tossed a little pebble at his window—he frowned, mistaking me for some irritating lady who wanted to get by him to exit. When he looked at me a second time and realized the irritating lady was his niece, his mustache rounded in surprise …

“My gawd, would you look at who it is!”

… and he became the uncle I adored once more.

First we talked football. And then we talked hearts.

“How’s your dad doing?” he asked.

I realized with a start that he didn’t know about my disownment. The Blue Band was exiting through the tunnel across the way, and I watched them go, avoiding my uncle’s hopeful expression. My voice caught in my throat. Jon speaks and smiles and sighs and gestures exactly like Dad.

“I don’t know,” I said, fighting for nonchalance, twisting the pendant on my necklace. “I guess he’s OK. No one has told me otherwise.”

He nodded. Paused. He and his mustache gazed across the field as the last of the tuba players lumbered out of sight.

“Well, you know how we are. You know how this family is. We never tell anyone what’s going on. Especially the serious stuff. Your aunt says we just disappear.”

“Oh, I know,” I said. “I know we do.”

I looked around. No one was left. We were the last of 110,000 fans to leave. Security guards were just rolling the big metal gates closed when we finally descended the ramp. I hugged and hugged and hugged Jon, and he didn’t seem to mind. He told me to tell everyone in North Carolina that he said hello, and I told him I would—knowing that I wouldn’t, knowing that I couldn’t, knowing that the undertow would win.

I left that stadium crying softly, the same way I had entered it.

♣♣♣

It was 9 p.m. by the time Randy and I stumbled back across the fields of tailgating aftermath,1 dodging the discarded trash bags resting on the knobby ground on the way to our car. It was dark and empty and difficult to see, even with the portable lights and their loudly humming generators. I shoved my hands into the front pockets of my Happy Valley hoodie to warm them and gave a wide berth to a sanitation truck that had just rumbled onto the grass. It carried two workers who seemed, like me, misplaced in this eerie pasture of departed fans.

One of the jump-suited men hopped out of the truck’s cab and cupped his hands around his mouth to form a megaphone, booming inaudible words in my direction. I assumed I was in the way of their work, so I walked even farther around him and the equipment his partner was pulling from the back.

He tried again.

This time, I heard him clearly across the decades: a goodbye, a hello, a friendly arm around my shoulder. A phrase that sounded an awful lot like belonging. Like family.

“We are!” he yelled.

Oh.

Oh.

“Penn State!” I cheered in return. ♣

*In general, I change the names of family members, etc., in this newsletter—to protect all my sinners and saints and loved ones and missed ones.

For more on this Carolina girl’s history of growing up with Penn State football, see my interview with Pat Forde of SI, “No Trash, Just Talk;” my essay on family, sports, and values, “Mythologies;” and my coming-of-age memoir chapter, “Thirteen.”

NEXT WEEK: “We Were,” an Intrepid Post on insecurity, identity, and my family’s false narrative of empowerment.

After losing my ID downtown, because the universe is committed to irony.